By what terms can an -ism or 'style' be discussed and evaluated?

Before trying to define a movement that has become an -ism, I will look at how these topics are usually discussed, and the pitfalls of this method, with a suggestion of a more effective way.

The First Mistake

To begin, I will address the most common mistake I see when it comes to defining and evaluating any movement that has become an -ism (e.g. modern-ism, minimal-ism, etc.) which is that the consequences of the movement are attributed as the definition of said movement.

For instance, iconic examples of Modern architecture tend to share similar features: prominent use of glass, steel, and concrete, as well as the use of simple shapes lacking in decoration, etc. However, while common, these features do not define a Modern building, instead, they are consequences of Modern thought and decision making, which will be discussed in more detail in my post on Modernity.

The important take away, is that awareness of cause and effect is essential when discussing any movement that has had the misfortune of becoming an -ism or 'style'. The effects of a cause do not define the cause. An analogy would be that there are many ways to reach the number 64. One could multiply 2 by 32, subtract 87 from 151, etc. Thus, the number 64 gives you little insight into understanding the cause that lead to its existence (multiplication, division, etc.)

The Second Mistake

The second mistake follows from the first.

Due to defining a movement by the characteristics of its output (thus, turning it into an -ism), it is easy to determine a 'check-list' for creating a piece in that 'style' and ignore alternative outputs that do not fit into this narrow view. This is not an issues when discussing all media, as it tends not to happen quite as much in the realm of 'fine' arts (painting, sculpture, film, etc.), and is instead often confined to the 'applied' arts.

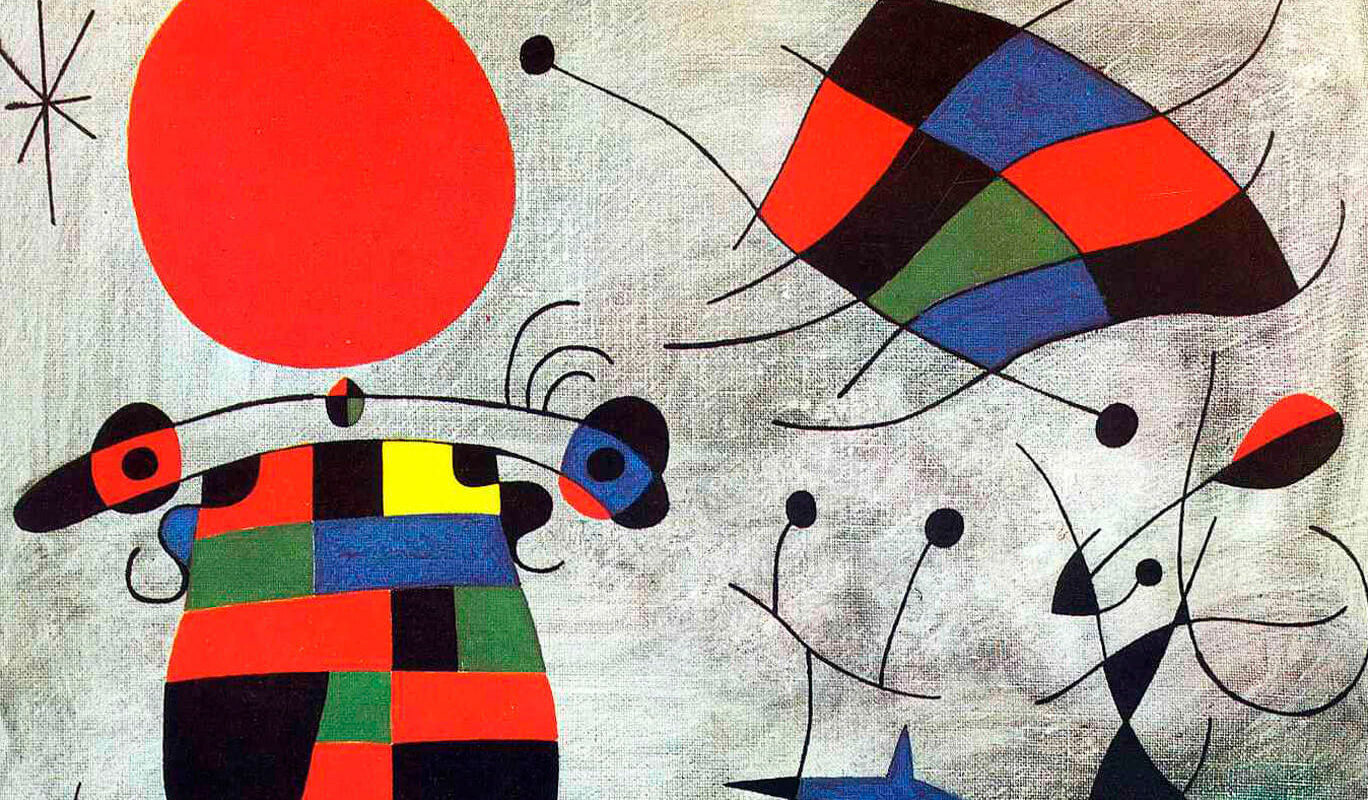

For example, many are ready to accept a Picasso, a Miro, and a Warhol as equally representative outputs of Modern ideals despite them having little immediately identifiable shared characteristics beyond the paint-on-canvas medium.

However, when it comes to architecture or product design, the -ism tends to overshadow the intent of the movement and the product becomes the result of a check-list.

For example, Le Corbusier is an often used example of quintessential modern architecture (frequently shown in a negative context), with his use of relatively simple shapes, hard corners, limited color palette, and open-plan living spaces. Despite his fame (or infamy), his work is but one example of valid and authentic output of the Modern movement and time.

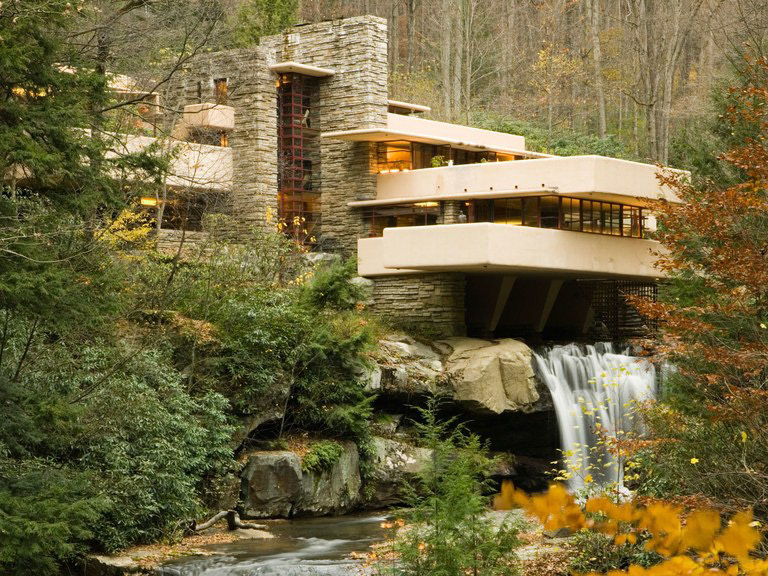

Another well-known (and arguably of longer lasting influence) Modern architect is Frank Lloyd Wright who's work could largely be described as 'warmer' and features more ornament (as distinct from decoration). While there are certainly similarities between his work and Corbusier's, it is clear that many of his outputs are all-together distinct and certainly do not satisfy the same check-list as one could conceive from Corbusier's work.

My aim is not to compare these two architects in depth or even to suggest that they are particularly disparate outputs of the Modern movement, but to illustrate the fallacy of trying to take a movement that stemmed from a way of thinking and approaching different circumstances in life, and shrink it into a check-list of visual characteristics.

Conclusion

In conclusion, what I propose is, when trying to define, evaluate, or discuss a product of a movement, try to understand the forces at work that lead to the movement, and remain conscious of the fact that an object is not a mere sum of its immediate parts, but the result of many experiences, processes, and intentions.

Reading List

The Search for Form in Art and Architecture - Eliel Saarinen